Constructing a character

with objects

Using

personal objects in art means the construction of a character in its most

intimate ways. Even if the personal objects belong to the artist, there is a

construction of the character of the artist; the projection of his/her persona

in specific contexts. For example, Hale Tenger’s large scale installation Sandık Odası (1997) turns the exhibition

space into the inside of a home, partly based on a past home of hers. It

carries the context of 80s Turkey, its political and cultural environment into

a personal space. Each object points towards a certain feeling, and is powered

by the artist’s memories and curation. The personal objects and memories

suggest the collective memory of a culture.

Hale Tenger, Sandık Odası, 1997

Ilya

Kabakov’s The Man Who Never Threw

Anything Away (1996) is another example of character constructing through

objects. As the title of the work strongly suggests, Kabakov’s imaginary

character holds on to every item he owns, in the effort to hold on to every

memory. The objects connect to each other to form a meaningful whole, an

archive of a life. Each object is carefully documented with a little note next

to it; enhancing the idea that this is indeed an archive. In contrast to

Tenger’s Sandık Odası, the space is

organized almost like a museum, with displays and explanatory captions. The

title of the work suggests the act of hoarding, but the display and

organization contradicts this premise. The viewer is forced to assume that each

object, however mundane, carries a meaning.

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away, 1996

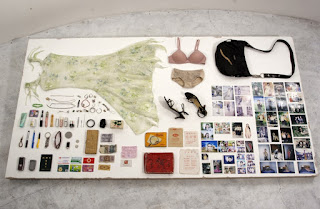

In Liu

Chuang’s Buying Everything On You (2006-present),

it is the viewer that constructs, or imagines the character. Chuang offers money

to strangers on the street in exchange for everything they have on them at that

moment. The result is a display of neatly arranged items on a white surface:

wallets, clothes, underwear, phones, keys, receits, shoes, etc. Like Kabakov’s

objects, Chuang’s displays are also too

neat, like they have been recovered from a crime scene and layed out on the

table for registration and examination. The eerie display of these objects

enhances the viewer’s urge to ‘investigate’ this absent owner and imagine a

character based on the evidence.

Liu Chuang, Buying Everything On You, 2006-present