Objects and identity

Objects

have a very significant place in psychology. From early childhood on, one

starts to identify with objects and form bonds. The wide known example of this

is the transitional object or comfort object introduced by Donald

Winnicott. This object, usually a

blanket, becomes a substitute for the early mother-child connection and serves

as a comforting item. The child uses the object during its transitional period

from the psychic reality to the external reality in which it grasps the separation

between itself and the external world.

In

adolescence, ownership and accumulation of objects is established. Adolescence

is a phase in which one’s identity is shaping and one’s life transitioning.

During this period, dependence on personal objects peaks. The reminding and

reminiscing aspects of objects are amplified due to the need for affirming one’s

life-story and past. Objects help construct a narrative and reassure one’s

identity and autobiography by reminding the person of past events and significant people in their lives. These factors support the idea that personal objects become more

significant during such transition periods and at old age.*

Contrary

to keeping and caring for objects, the act of getting rid of them is also

significant in psychology. Although the notion of decluttering is reinforced as an antidote to hoarding, the urge to

throw personal objects away is also rooted in the complicated and strong

relationship people have with their objects; much like collecting or hoarding.

Throwing things away is an attempt at a rejection of the dependency on objects;

while keeping them is to accept this dependency and to immerse in it.

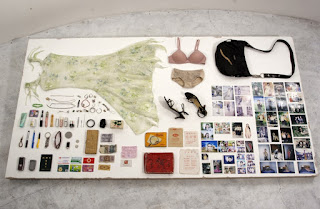

Taking

personal objects and using them in artwork is also a way of dealing with

objects and one’s relationship with them. To transform these objects into

artwork and to offer them as display

-even when they are someone else’s things- is the artist’s way of

responding to the bond people have with objects.

Sources

*Habermas, T., & Paha, C. (2002.). Souvenirs and other

personal objects: Reminding of past events and significant others in the

transition to university. In J. D. Webster & B. K. Haight (Eds.), Critical

Advances in Reminiscence Work (p.123-138). New York: Springer.